Contents :

- Three short essays/commentaries addressed to Simon Gales by Ian Jeffrey

- Turps Banana magazine review on Simon Gales

- Simon Gales 'studio visit' essay by Phil King

- 2018 Jane Harris Out There Eagle Gallery, London, review by Simon Gales for Saturation Point editorial magazine (Please scroll down to the review or access the link to Saturation Point here http://www.saturationpoint.org.uk/Jane_Harris_Eagle.HTML)

OFF LIMITS

I looked at your exhibition in THE FACTORY, but not closely enough. It was a good site for such an exhibition, with graphic virtuosi working beyond the wall of scaffold boards - by law they only have a certain useful life (the boards, that is). I wondered about the angle grinder but couldn't find an Achille supplier on the internet - perhaps an archaic French brand ousted by Makita. They make a terrible noise and a lot of dust, and you have to concentrate hard on the action of the machine - likewise with chain saws and hedge cutters. You could say that they overwhelm the ego or take up its entire attention. After the event you stand back and compose yourself in silence to see if the cut or slice is straight - or straight enough. You use your judgement. It is procedural, time aware work - if you care to think about it. I thought as far as the story of Achilles and the tortoise - the story cropped up in the back of my mind. Maybe I was prompted by the tortoise shell look/shape to the cover on the Achille machine.

Then there was the arrangement with the Republican elephant and the banana emoji - datable - you date the construction to 2018. The banana stands for excitement or wow factor (I see) and is soon over but you have painted it studiously - likewise the shadowy elephant. The GOP is supposed to move very slowly and deliberately like an elephant. I guess your iconography concerns itself with variations in pace. The wooden battens balance and they imply adjustment and judgement, which takes time and care. There is the question of assessment - to see if you are dealing with the tangible or the depicted. I noticed that you had hung the Achille (noisy - and demanding of committed attention when in use) under the obviously painted surveillance camera, an epitome of non-presence and non-interference - and a contemporary embodiment of study (at least in TV crime series that I see). I sometimes see disregarded banks of monitoring screens in surveillance booths in institutions - and register such set ups as signs of the times.

You invite onlookers (me anyway) to follow your thinking - or at least to register that you have been thinking and that you calculate as you make your arrangements, adjusting real and painted shadows. What would the assemblages look like in different lighting - in more diffused lighting, for example? At the same time I would say they are companionable works, for we have all dealt with slender bits of wood, planks and boards along with painted backgrounds. You also add to the mixture with passages of virtuoso painting - such as the hanging carcass.

You mentioned Zurbaran - who was attentive to and had to deal with anachronism. As a committed realist he must have been intrigued by the problem of representing dreams, anticipations and recollections. My journey back from the Factory and London Road to Liverpool Street was, you might say, Zurbaranesque, for I had to recall the route backwards, following in my own footsteps, with changes at Piccadilly Circus and Holborn along with the swirling area around the Elephant and Castle.

I would like to have seen the Giacometti with coloured pullover, tie, shirt and stone hair, occupying that very slight black gap in the foreground of the rectangle. Becket was pixelated, would you call it, as if the signal had been interrupted and distorted - but I only have the screen image to go on. It is interesting to remember that the proceedings, as I saw them, were marked by the absence of Richard Wentworth - and the presence of Lala's sisters. Waiting for Richard, I looked across and saw a dark silhouetted figure in the intermittent light in the space, and didn't at first recognise that it was Lala.* It was like one of your portrait transformations.

Ian Jeffrey 2019-09-23

GIACOMETTI and BECKETT

I was thinking about your paintings, in progress, of Giacometti and Beckett. You had chosen them as topics, I believe, because they have similar sparse approaches to their material. Beckett illustrates fundamental conditions and Giacometti deals in cores and outlines. It wasn't just a question of selecting any notable who had ever been photographed. It also seemed important that both had been photographed. You then turned the positives into negatives - and that seemed significant. A negative is a restrained kind of photograph, one in which all the empirical details are reduced - to make something like a dream image, even a concept - it might once have been called. Of course all the details are there but they are subsumed or just blended. Positive printing brings details to the surface and returns the picture to the natural world in which garments and textures can be identified - along with skin textures and features. It is easier to deal with familiar natural matters, such as the cut of a jacket or a hairstyle. In the more evanescent negative images these natural details are incorporated and somewhat dissolved, turning the figure into a ghost or even a trace.

Looking at both pictures originally I had an idea or sense of their identities disturbed somewhat by an interest in the colour of Giacometti's shirt and pullover. I thought that you were presenting me with a scale operating between the distractions of natural and singular things at the lower end and concepts at the upper. I didn't think that you were insisting on the scale but rather remarking on the varieties of ways in which we know things - seeing, remembering, judging, anticipating. I noticed in the Avedon originals for Beckett that the second image shows him turning away - having attended to the camera he is now attending to something inward - there is some suggestion of that anyway. The counterpart to Giacometti, to the left, is a slightly indented disc - a movement from a diagram to a form, another embodiment of the transition and difference that I have just mentioned. Giacometti's clothing and hair also appear as in low relief in greyish stone. It asks me to think of the portrait both sculpted and tinted, or as made up of materials that might be touched - a knitted pullover in contrast to carved folds in stone. Your gift, I think, is to manage these shifts discreetly - so that I am just alert to them - as I am just alert to the idea of the sculptor and the writer. I imagine that both portraits are thinly painted, for there is a papery look and feel to the Giacometti - barely tangible. Remember, though, that I have only seen them on screen.

Ian Jeffrey 2019-10-06

NICODEMUS

The power of Y. It reminded me of a lot of urinals with brownish water-staining under the flush outlets, plus discarded chewing gum and so on. It must be a French arrangement to have the flow controlled by a lever. In G.B. it would probably be unthinkable, for it would be left running or wrenched off. Some of my pipes have a flow control managed by a valve operated by a screwdriver - in case the washers give out, or their seatings. But I don't think that your subject is entirely plumbing, although it is that to some degree. I do, however, approach such fixtures and adjust myself with regard to distance and angle, and having adjusted my dress I would then reach forward with my right hand to operate the flush. Peeing is something of a regular ballet or a manoeuvre at least. You could put it on a long list of commonplace manoeuvres along with getting a timed ticket in a car-park - more long winded that and less precise. My life, when I think of it, is made up of these set-pieces that change slightly with circumstances..

So? Well not long ago I was looking at pictures by Candida Hofer, a Dusseldorf photographer, and noticed that she had taken a picture of a painting by Holbein in the art museum in Basle. It is of the dead Christ laid on a slab - a long low framed picture. Discreetly in the scene she has included an air vent let into the wall, part of the museum's air conditioning I imagine, but a reminder that the dead body of Christ would have smelled. It is also a reminder of air, or of breathing and of the air breathed by the living. There is another wonderful picture by Struth of two people in the Accademia looking at that very late Deposition by Titian. Christ is held by the Virgin - and Nicodemus (played by Titian) reaches forward to touch His hand, as if to confirm that He is dead. Of course He is, for the body is greyish. Struth's stroke, though, is to notice a small radiator in the foreground in the gallery, just to the left of the visitors on the seat. It looks like no more than a bit of the furnishings but it too is a reminder of warmth and living, of that condition that Nicodemus was recalling and regretting.

Go on! Hofer reminded me that I am still alive, still breathing - an important part of that business of living. Struth noted warmth as another of these necessary conditions. We probably overlook such obvious factors, but they are crucial to Being - more rooted certainly than our beliefs and points of view. I would put your delicate implied ballet in the same category of reminders of these basic conditions. You, like Struth and Hofer, have made an arrangement that allows me, or anyone else, to re-enact a procedure, or just to become aware of it in retrospect. It is an elemental state beyond - part of the commonplace, but deeper into it. Maybe it can be described or defined through empathy. Not long before coming in to type this note I put a fire on in my main room - a big wood-burning stove that takes some time to get going. It heats up, first the surrounding air, and then the material surrounds. The cat, a devotee of warmth, waits for the slate slab in front of the fire to warm up, drowses on it and then moves away by degrees as things hot up. I look forward to this creaturely procedure/performance of warming up and adjusting for the sake of ease and comfort. At some point I realised what I was doing. I stood back and analysed my actions without really intending to. I see your scene as a schematic version of this kind of real-life procedure. It has an ethical aspect (your image) as a reminder of an underlying part of one's or our nature - there is something redemptive about it I think. It is like a score for a basic performance - the sort of performance that we carry out day in and day out without registering or looking at it critically or thoughtfully.

Ian Jeffrey 2019-10-22

Reproduced with the kind permission of Ian Jeffrey.

Ian Jeffrey is a former Goldsmiths tutor and art historian, publications include:

The foreword for Freeze, 1988; The Real Thing: An Anthology of British Photographs 1840-1950, London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1974.Photography: A Concise History. London: Thames & Hudson, 1981; The British Landscape 1920-1950. London: Thames & Hudson, 1984; Timeframes: The Story of Photography. New York City: Watson-Guptill, 1998; An American Journey: The Photography of William England. Munich; New York; London: Prestel, 1999; Revisions: An Alternative History of Photography Bradford: National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, 1999; The Photography Book. London: Phaidon, 2005; Second, revised edition. London: Phaidon, 2014; How to Read a Photograph: Understanding, Interpreting and Enjoying the Great Photographers. London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.

*Note Lala Meredith-Vula artist and photographer

by Phil King

Studio Visit

Studio visits can be both unnerving and consoling experiences. Away from the intensity of art school studio visits, where looking itself is a pedagogical event, the experience of art in a studio setting has no clear goal. It is a form of sharing, a mutual discovery of problems, not for a tenable purpose but simply to provide a sense of mutual finding out, of experience itself. The artist can explain, guide even try and convince but they know that it is the work itself, a work that is often in a mutable condition, that is convincing. Or not. In the studio of accomplished artists there is an edge between their art's absolute nature and the visitor's experience.

Simon Gales's paintings take time. By saying this I deliberately desire to evoke a sense of removal, of taking away.

The paintings literally take time away. In his studio, in discussion, I begin to intuit that he actually achieves this removal of time in different ways. The work resists spectacle, offers another time and place apart the rush of contemporary states, a hard won margin noticed through a kind of resistant contemplation, a sort of impossible sovereignty.

Within their pictures, enact a certain control, a certain reduction of the world to a manageable history of their own making. Painting itself occurs in the drama between these two poles. Simon Gales's painting heightens and combines the different lights into an almost engineered unity.

The architecture of his work replaces painterly tectonics, the armature of classical western painting, with actual construction. He constructs an actual painterly field, wooden reliefs that speak of the purity of modern relief, of Ben Nicholson's solutions perhaps. These supports, paintings in themselves capture light freely, part of everyday days, nailed by artificial light, softened by the rise and fall of different daylights.

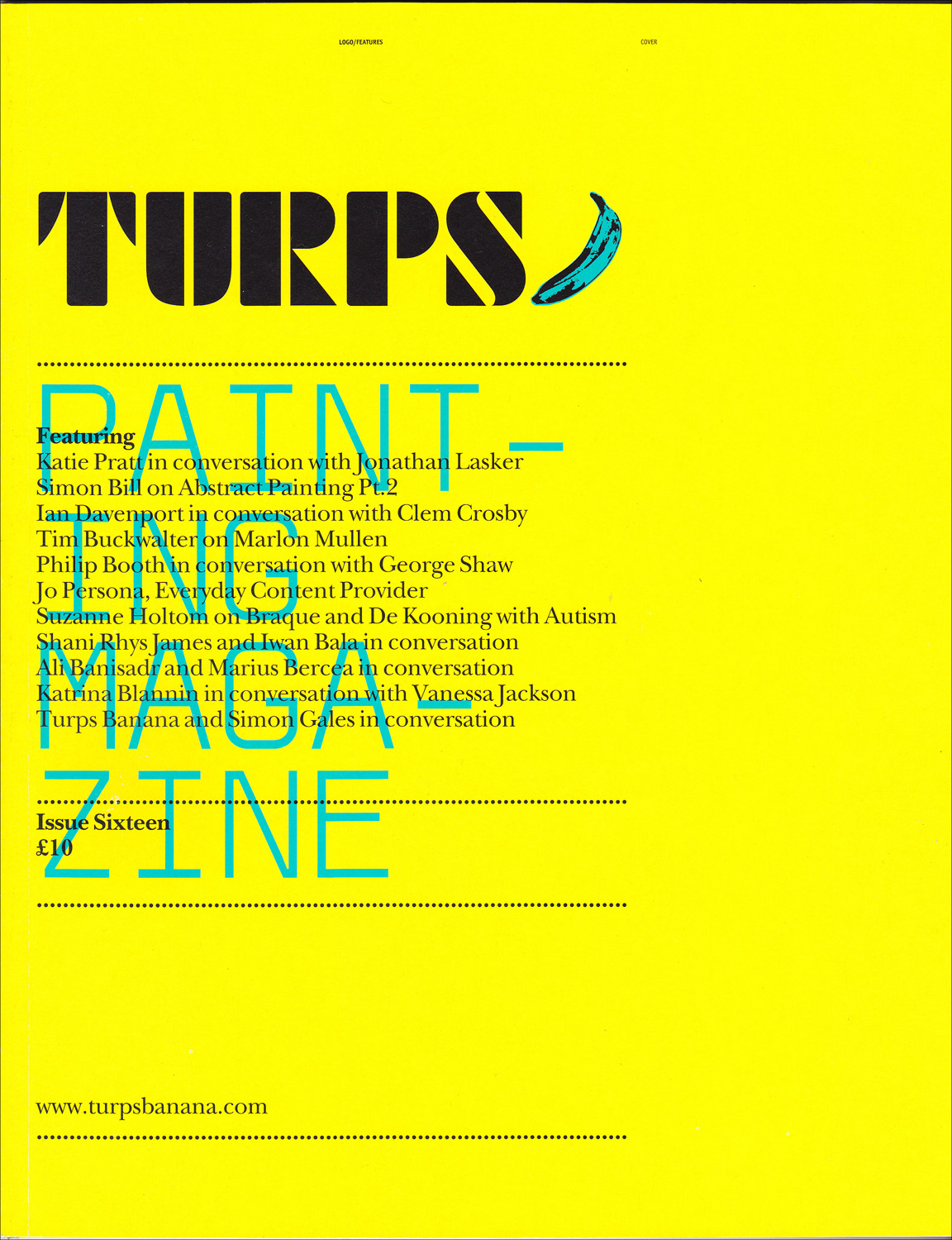

I think, I speculate, that it is patience, the control and use of time, the taking of time itself, that enables the signifying event of his painting, the painting of animals and figures across the carefully constructed and tended fields that he prepares. Fugitives that bring with them their own surrounding light and space, in the case of a bird literally stirring the represented air into forceful existence even as it leaves the picture behind.

Because Gales's painting acknowledges the violence of the shuttered capture, the photo cliche as violent grasp, the arrest, and represents it mindfully across the light capturing surfaces he nurtures, it speaks of a certain impact even though that impact is softened in time, softened by the thoughtful stroke of the brush. Two coexistent spaces clash and yet that clash is sublimated, giving rise, in my mind, to a sublime impression of fluidity.

Time, in another time, was said to flow. Far from the catastrophic almost epileptic demands of contemporary existence, from its exclusive demands and divisions, we sense that time passes slowly and yet we rarely fall into that stream. These paintings, as painting does in its continual balance between surrender and control, allow access to both actuality and representation, they do so with a deceptively muted cymbal clash, each painting a moment of surprise, of relief, of humour in the corner of an eye.

Studio visits are uncanny experiences and take time to digest and process, words both fail there and break through.

Thoughts are both articulated and compromised, lost and found, they are put on edge, and it is later that the realisation that it is paintings basic forces at work, disruptive, unarguable and yet demanding of response, that creates and provokes thought itself, in yet another time.

Phil King 2014

Phil King is an artist and writer of numerous essays and a translator of Jean Genet's "Studio of Giacometti" published by Grey Tiger Books 2014

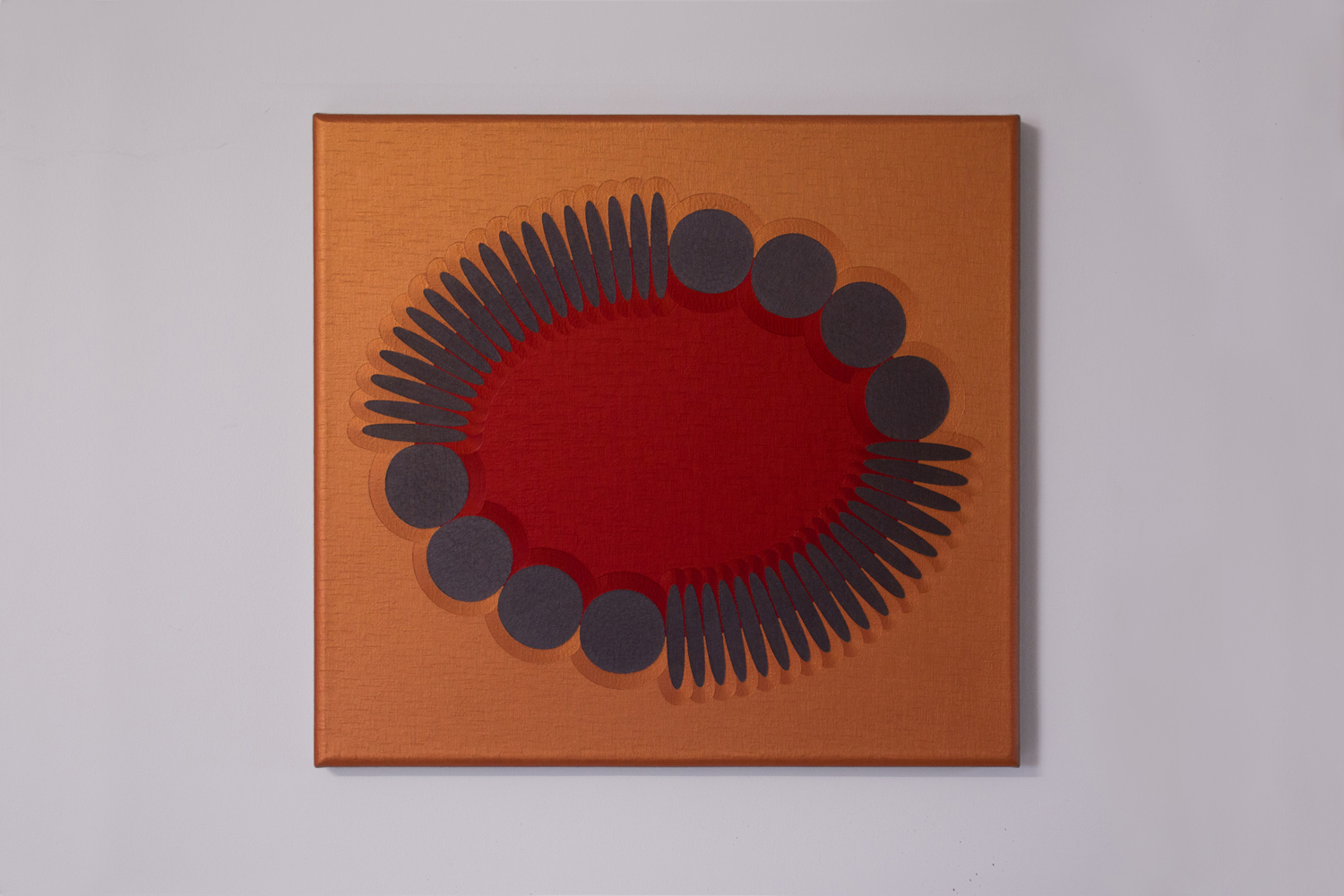

Jane Harris | OUT THERE

Eagle Gallery, 15 March - 14 April 2018

Review by Simon Gales

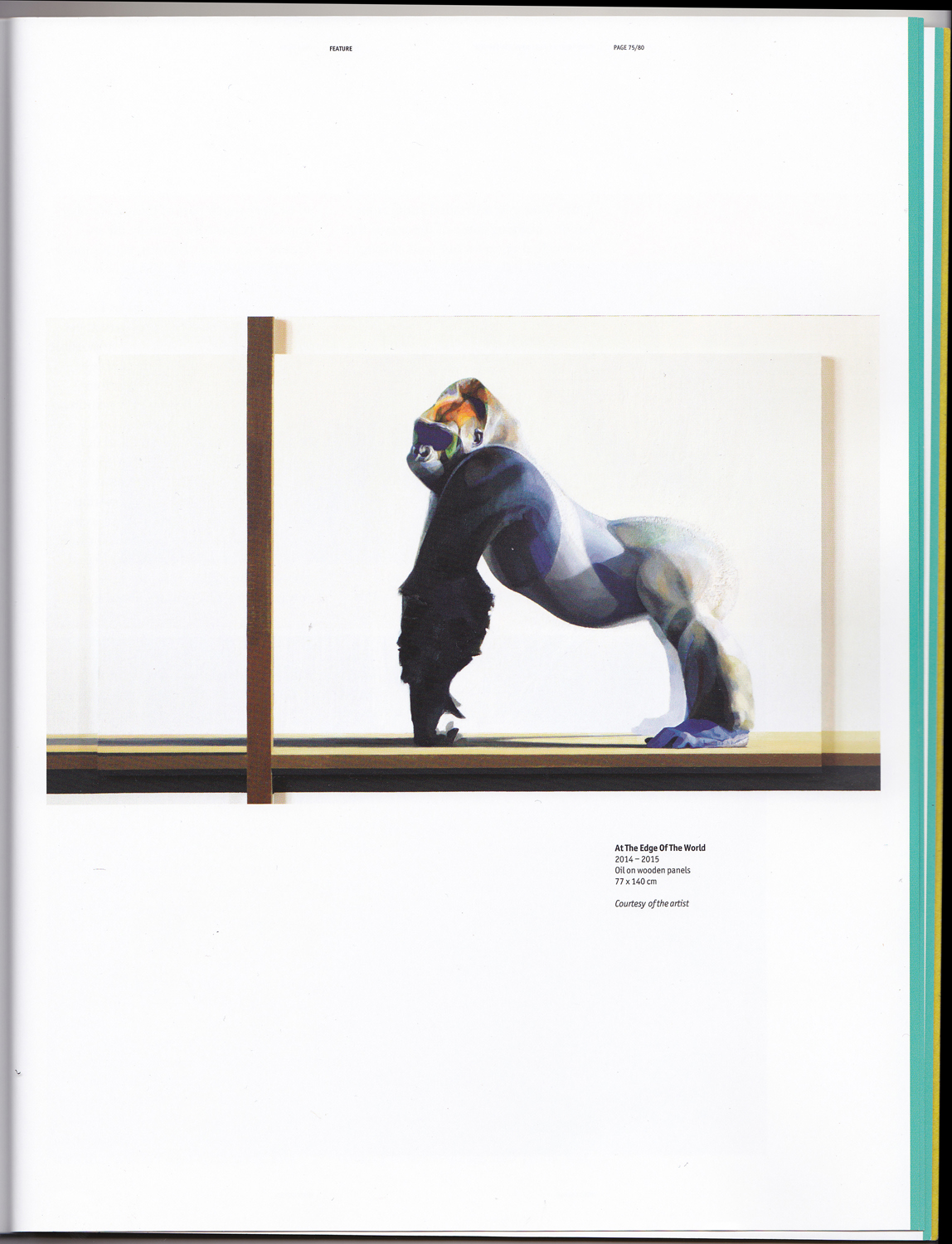

Stepping out across the floor towards the centre of Emma Hill's Eagle Gallery, one gets an instant impression that work and wall were created simultaneously. The restrictions of the space seem to be pushed out by paintings, mostly square in format, to create an exhibition that looks surprisingly large. There is a strange sensation at that point: even before the works start to register, Jane Harris has already enveloped the spectator in an environment where dimensions start to shift and change. Each piece - seemingly non-figurative - appeals in turn, magnetically pulling via a powerful vortex of colour and an extraordinary virtuosity in paintwork that are together entwined and enticingly meted out to reel us into uncharted water.

Eagle Gallery Space with Strike Out, Wild Thing and Either Way

It takes time to ascertain what it is that is drawing me towards these paintings. The silvery-green jade exterior and deep ultramarine interior in Turning Points is certainly alluring, but there is also something incredibly compelling in the recurrent elliptical shapes that orbit the inner form or void, strung together to make a larger aperture or motif. This cellular structure of consecutive ellipses is set as if spring-loaded and held in place, both externally and internally, by a wide continuous brush mark, a contour that appears either proud or recessed, and applying what seems to be an equal pressure all round. As I am drawn closer, it becomes apparent that the tension is released at five points but gives way slightly at one side. It is as if the painting is beginning to develop a kind of precariousness that provokes unease, instability and imminent collapse, checking a possible yearning in the viewer to reach out to the deep blue beyond.

Turning Points, 2017, oil on wood, 40 x 40 cm

There is a pronounced physicality, often enhanced by the metallic hardness of surface in some of the paintings, which is either impressed or lifted by the continuous brush strokes supporting the motif. It takes a moment to register which way it is, until with a slight shift of position the sudden change of light hitting the surface reverses the tones to the opposite, and instantly the spectator is wrong-footed. It is as if one is forced to question one's senses, an uncertainty that becomes compounded when confronted with the multiple pieces such as the quadriptych Letting Slip (Four Small Blasts). For it suddenly dawns on me at this point that although all paintings will alter according to the light, from morning to afternoon, Letting Slip is perpetually changing by the second, let alone by the time of day. However much this is intentionally manipulated by the artist from one piece to another, there is in real time a past, present and future, with the hot cores beyond constantly alternating in intensity as if by the degree, expanding and contracting.

.jpg)

Letting Slip (Four Small Blasts) - quadripty, 2017, oil on wood, 80 x 80 cm

The way these paintings are put together, the paintwork in particular being quite spectacular, it is difficult in many respects to fathom how it is humanly possible to paint an uninterrupted broad brushstroke, perfect in width and without flaw, that waves and circles each ellipse, seemingly at speed. It is as if the paintings are devoid of human intervention, that they are in fact entities, literally living things, cellular, monocular, even distinctly organic in structure. In Wild Thing the orange centre is regenerative and rising, the green ovals seem to swell and enlarge, flourishing against the blue-black like a bursting thistle. Similarly, in Night Ride there is a strong sense of sensuality, the warm pink interior seeping around the dilating ovular shapes until there is a sudden change of light, when the motif is either projected into the space of the spectator or recedes deeper, almost teasingly. The paradox is that the mood rapidly evaporates when one notices the five earth-brown ellipses, squeezed to form spikes and expose a potential that makes one hesitate, even withdraw cautiously.

.jpg)

Wild Thing, 2018, oil on wood, 80 x 80 cm

Night Ride, 2017, oil on wood, 50 x 50 cm

Apart from the fields of short interconnecting and pulsating strokes of colour that almost electrically relay across one painting and down another, particularly visible in the multiple works such as Letting Slip, Either Way and Outlandish, it is clear that there are no other straight lines in any Jane Harris painting. Rather, there is a carefully orchestrated, virtually musical rhythm of curves and ellipses, hemispheres that have no beginning and no end. Holding Back is a breathtakingly powerful and colourful work with its sumptuous, plush, vibrant metallic orange and crimson interior, colours that seem to enhance an equally beautiful, almost astronomical, physical and mathematical force at play. Slightly distorted spheres and ellipses appear punched into the shimmering surfaces of opposing pressure that are tightening under the strain and sheening the bevelled edges of the painting.

Holding Back, 2017, oil on linen, 58 x 64 cm

But these are impressions one gets from images that are so meticulously put together that I begin to wonder whether one is intentionally coerced into seeing things that may not necessarily be there. That perhaps one is tricked into perceiving these things as clear-cut as the paintings themselves. As the paintings change according to the light, one senses voids one second - and then it is as if the door suddenly closes to a definite surface the next. I get the impression that maybe one is entranced in a kind of narcotic deception, transparently given off by hypnotic artworks that have us totally under their control.